Approach

As long as the below two conditions hold, we can use Dynamic Programming to solve a problem:

- Sub-problem: We can formulate the solution to the original problem as a function of the solutions to “smaller” versions or sub-problems. The “smallest” sub-problems are trivially solved.

- Order: A DAG (explicit or implicit) exists such that:

Node: One node represents one sub-problem.Edge: There is an edge fromto

if computing solution to the

requires that the solution to the

is already available.

- Must process the nodes in a topologically sorted order.

Given such a DAG, the overall approach is as follows:

def solve(DAG):

solutions = []

solve_trivial_subproblems(solutions)

sorted_nodes = topologically_sort(DAG)

for node_i in sorted_nodes:

solutions[node_i] = func1( { solution[node_j]: There is an edge from node_j to node_i } )

# Original problem's solution appears in solutions

return func2(solutions)

Observations

- We do not need to perform the topological sorting explicitly. If the inputs to the original problem allow computations to be organized such that we end up processing nodes (or sub-problems) in topologically sorted order, that suffices.

- By processing each node (or sub-problem) in topologically sorted order, we can be sure that the solutions to the sub-problems that are required for the current node to be solved, are all available. As a result, for overlapping sub-problems, memoization helps.

func1is recursive. Going top-down is simpler because the topological order is inferred fromfunc1on a need-to-know basis. For bottom-up, we need to know the topological order for the entire DAG beforehand.- The total complexity is at least as large as the number of nodes. However, the complexity could actually be dictated by the total number of edges. Because, the total number of edges determines the cost of evaluating

func1, the body of the loop. Given the same number of nodes, a dense DAG is computationally more expensive than a sparse DAG. - For optimization problems, where

func1andfunc2aremaxormin, eachsolution[node_i]has a unique ancestorsolution[node_j]. In other words, there is a path (from left to right) throughsorted_nodesthat leads up tosolution[node_i]. To be able to re-construct this path, we could save eachsolution[node_i]‘s ancestor. - Even if a directed graph seems to exist among the sub-problems, it may not be immediately clear whether it contains a cycle. Since a directed graph is a DAG if and only if it has a topological ordering, it might be easier to approach the problem from the opposite direction. In other words, if there is an inherent order among the sub-problems, it could indicate the presence of a DAG. Trivially solved problems are at the root of the DAG which may suggest how to process the nodes respecting topological order.

Explicit DAG

Shortest paths

Given a DAG with positive edge weights and a source node, we want to find shortest path distances to every other node from that source node.

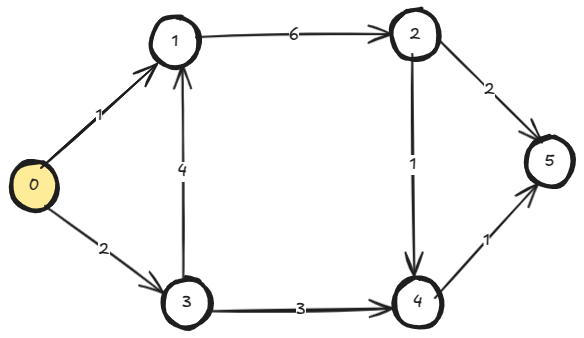

In the below DAG, the node 0 is the source.

We can use Dynamic Programming to solve the problem. Because:

- Sub-problem: We can formulate the original problem in terms of sub-problems. For example, to be able to reach the node 4, we must either go to node 2 or node 3 first. So, short_dist(4) = min( short_dist(2)+1, short_dist(3)+3 ). The short_dist(0) is trivially solved.

- Order: The input itself is a DAG. So, we explicitly do topological sorting and process the nodes in the sorted order.

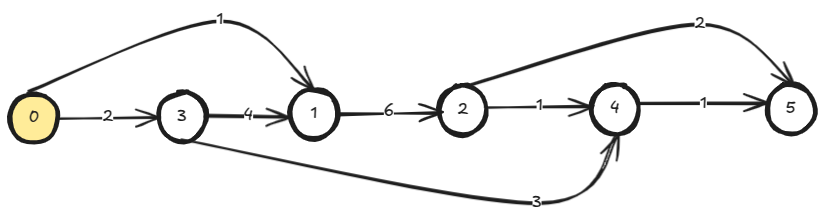

We do topological sorting first.

from collections import deque

def topo_sort(adj_list: List[List[int]]) -> List[int]:

n = len(adj_list)

visited = [False] * n

topo = deque()

def dfs(u: int) -> None:

visited[u] = True

for v, _ in adj_list[u]:

if visited[v]:

continue

dfs(v)

topo.appendleft(u)

for u in range(n):

if visited[u]:

continue

dfs(u)

return list(topo)

adj_list = [

[ [1, 1], [3, 2] ],

[ [2, 6] ],

[ [4, 1], [5, 2] ],

[ [1, 4], [4, 3] ],

[ [5, 1] ],

[]

]

sorted_nodes = topo_sort( adj_list )

print(f"{sorted_nodes=}")

# sorted_nodes=[0, 3, 1, 2, 4, 5]

We solve the nodes or sub-problems in the sorted order. Here func1 is and

func2 is identity.

n = len(adj_list)

dp = [float('inf')] * n

# Solve trivial sub-problem

dp[0] = 0

# Sort topologically

sorted_nodes = topo_sort( adj_list )

for v in sorted_nodes[1:]:

for u in range(n):

edges_from_u = adj_list[u]

for to, w in edges_from_u:

# Found an edge to current node v

if to == v:

dp[v] = min( dp[v], dp[u]+w )

print(f"{dp=}")

# dp=[0, 1, 7, 2, 5, 6]

Since func1 is , we can save ancestors to be able to re-construct the actual path to a node.

from typing import Optional

def construct_path(current: int, ancestors: List[Optional[int]]) -> List[int]:

path = deque()

path.appendleft(current)

while (prev := ancestors[current]):

current = prev

path.appendleft(current)

path.appendleft(0)

return list(path)

adj_list = [

[ [1, 1], [3, 2] ],

[ [2, 6] ],

[ [4, 1], [5, 2] ],

[ [1, 4], [4, 3] ],

[ [5, 1] ],

[]

]

n = len(adj_list)

dp = [float('inf')] * n

ancestors = [None] * n

# Solve trivial sub-problem

dp[0] = 0

# Sort topologically

sorted_nodes = topo_sort( adj_list )

for v in sorted_nodes[1:]:

for u in range(n):

edges_from_u = adj_list[u]

for to, w in edges_from_u:

# Found an edge to current node v

if to == v:

if (updated_dist := dp[u]+w) < dp[v]:

dp[v] = updated_dist

ancestors[v] = u

print(f"Shortest distance path to node 5: {construct_path(5, ancestors)}")

# Shortest distance path to node 5: [0, 3, 4, 5]

Implicit DAG

Very first question for a DP problem is: what are the sub-problems? Below example problems are in five categories. All problems in a category define the sub-problem similarly:

- Prefix as sub-problem

- Pair of prefixes as sub-problem

- Knapsack

- Subarray as sub-problem

- Subtree as sub-problem

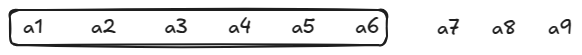

Prefix as sub-problem

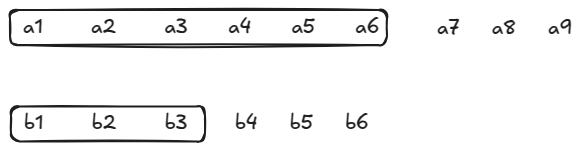

Input is and a sub-problem is

.

Number of subproblems: .

Longest increasing sub-sequence

Given a sequence of numbers, we want to find the length of the longest increasing (left-to-right) sub-sequence in it.

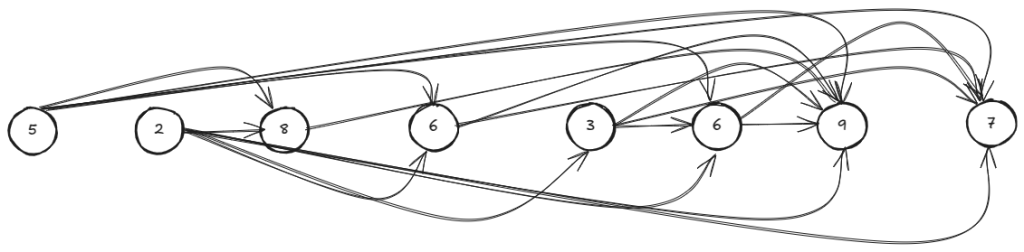

For the sequence [5, 2, 8, 6, 3, 6, 9, 7], an increasing sub-sequence is [5, 8] but this is not the longest possible sub-sequence.

We can solve the problem using Dynamic Programming, because:

- Sub-problem: solutions[ seq[0…i] ] = 1 + max( { solutions[ seq[0…j] ]: j < i } ), solutions[ seq[0…0] ] is trivially solved.

- Order: solutions[ seq[0…i] ] does not consider the numbers seq[j] where j > i, so if we process the seq left-to-right, the directed edges will always go towards right and would define a topological order of the sub-problems. Therefore, it is a DAG.

The DAG is like below:

def find_longest_increasing_subsequence(seq: List[int]) -> int:

n = len(seq)

# Solve trivial sub-problems

dp = [1] + ([0] * (n-1))

# Process sub-problems in topologically sorted order

for i in range(1, n):

sub_problem_max = 0

for j in range(i-1, -1, -1):

# No edge from dp[j] to dp[i]

# So, dp[j] is not included as a input to func1

# func1 is max

if seq[i] <= seq[j]:

continue

sub_problem_max = max( sub_problem_max, dp[j] )

dp[i] = 1 + sub_problem_max

# func2 is max

return max(dp)

seq = [ 5, 2, 8, 6, 3, 6, 9, 7 ]

l = find_longest_increasing_subsequence( seq )

print(f"{l=}")

# l=4

Since func1 is , we can save ancestors to be able to reconstruct the longest increasing sub-sequence.

from typing import Tuple

def find_longest_increasing_subsequence(seq: List[int]) -> Tuple[int, List[int]]:

n = len(seq)

dp = [1] + ([0] * (n-1))

prev = [None] * n

for i in range(1, n):

sub_problem_max = 0

for j in range(i-1, -1, -1):

if seq[i] <= seq[j]:

continue

if dp[j] > sub_problem_max:

sub_problem_max = dp[j]

prev[i] = j

dp[i] = 1 + sub_problem_max

return dp.index(max(dp)), prev

def construct_subseq(seq: List[int], last_index: int, prev: List[int]) -> List[int]:

ls = [ seq[last_index] ]

curr = last_index

while prev[curr]:

curr = prev[curr]

ls.append( seq[curr] )

ls.reverse()

return ls

seq = [ 5, 2, 8, 6, 3, 6, 9, 7 ]

last_index, prev = find_longest_increasing_subsequence( seq )

ls = construct_subseq( seq, last_index, prev )

print( f"{ls=}" )

# ls=[2, 3, 6, 9]

Pair of prefixes as sub-problem

Input is and

. A sub-problem is a pair of prefixes:

and

.

Number of subproblems: .

Edit distance

Given a source string and a target string, we want to find the minimum cost to transform source into target. Three operations are allowed:

- Delete: We can delete a char from source string

- Insert: We can insert a char from target string into source string

- Replace: We can replace a char in source with a char in destination

Dynamic Programming can be used because:

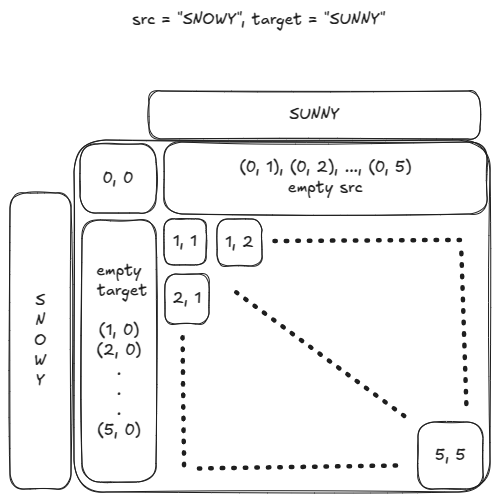

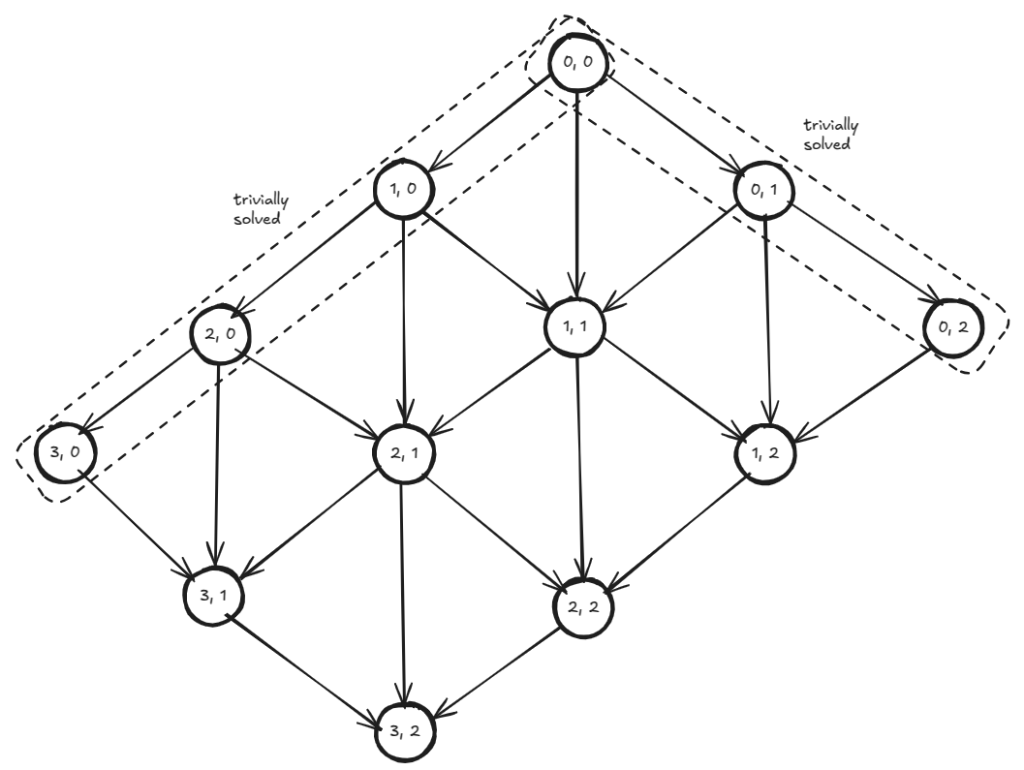

- Sub-problem: Say we have src[1…m] and target[1…n]. Looking at the last char from both strings, either we can delete src[m], we can insert target[n], or we can replace src[m] with target[n]. So, we define: solutions[ (src[0,1,…i], target[0,1,…j]) ] = min( { 1+solutions[ (src[0,1…i-1], target[0,1…j]) ], 1+solutions[(src[0,1…i], target[0,1…j-1])], delta(i, j)+solutions[(src[0,1…i-1], target[0,1…j-1])] : i <= m and j <= n } ) where diff(i, j) = 0 if src[i]==target[j] else 1. The solution to original problem is solutions[ (src[1…m], target[1…n]) ]. The sub-problems corresponding to empty src string (src[0…0]) or empty target string (target[0…0]) are trivially solved.

- Order: The sub-problems can be placed on a (m+1)-by-(n+1) like below. The first row corresponds to the sub-problems: { solutions[ (src[0…0], target[0…j]) ]: j <= n }. Similarly, the first column corresponds to the sub-problems: { solutions[ src[0…i], target[0…0] ]: i <= m }. The DAG’s nodes will be the coordinates of the cells and each node will have exactly three edges from other sub-problems.

The DAG would look like:

There isn’t a cycle, because all edges go strictly bottom-wards. We have several choices in processing the nodes (or sub-problems) and still maintain topological ordering. We can process each level from top to bottom which would be processing the grid one diagonal at a time. We can process each path going rightwards (grid’s row) or each path going leftwards (grid’s column).

from typing import List, Optional

def construct_ops(dp: List[List[int]], src: str, target: str) -> List[str]:

ops = []

i, j = len(dp)-1, len(dp[0])-1

while i > 0 and j > 0:

delete_cost = dp[i-1][j ] + 1

insert_cost = dp[i ][j-1] + 1

replace_cost = dp[i-1][j-1] + (0 if src[i-1] == target[j-1] else 1)

if dp[i][j] == delete_cost:

ops.append(f"delete {src[i-1]}")

i -= 1

elif dp[i][j] == insert_cost:

ops.append(f"insert {target[j-1]}")

j -= 1

else:

ops.append("no-op" if src[i-1] == target[j-1] else f"replace '{src[i-1]}' with '{target[j-1]}'")

i -= 1

j -= 1

ops.reverse()

return ops

def compute_edit_distance(src: str, target: str) -> Tuple[int, List[str]]:

m, n = len(src), len(target)

# src on y axis or vertical or rows

# target on x axis or horizontal or columns

# 0-th row corresponds to subproblems with empty src

# 0-th col corresponds to subproblems with empty target

# i-th row in dp corresponds to (i-1)-th char in src

# j-th col in dp corresponds to (j-1)-th char in target

dp = [

[0 for _ in range(n+1)] for _ in range(m+1)

]

# Solve trivial sub-problems

# Solve 0-th row, src is empty

# insert all chars from target into src to match target

for col in range(1, n+1):

dp[0][col] = dp[0][col-1] + 1

# target is empty

# Solve 0-th col, target is empty

# delete all chars from src to match target

for row in range(1, m+1):

dp[row][0] = dp[row-1][0] + 1

for row in range(1, m+1):

for col in range(1, n+1):

# Sub-problem (row, col) has edges from three sub-problems:

# 1. (row-1, col ): delete src char

# 2. (row, col-1): insert target char

# 3. (row-1, col-1): (may be) replace src char

# func1: min()

dp[row][col] = min(

dp[row-1][col ] + 1,

dp[row ][col-1] + 1,

dp[row-1][col-1] + (0 if src[row-1] == target[col-1] else 1)

)

# func2: select last cell

return dp[m][n], construct_ops(dp, src, target)

src, target = "SNOWY", "SUNNY"

edit_dist, ops = compute_edit_distance( src, target )

print(f"{edit_dist=}, {ops=}")

# edit_dist=3, ops=['no-op', 'insert U', 'no-op', "replace 'O' with 'N'", 'delete W', 'no-op']

Knapsack

Knapsack with repeat

Take items with weight () and value (

) in a knapsack that can carry a total weight of

with the goal of maximizing the total value in the knapsack. Every item has many copies. So, apart from the constraint on the knapsack’s total weight, there is no limit on how many copies of an item we can take.

Sub-problem

.

We take .

Order

Increasing order of .

With items, time:

, space:

.

def knapsack_with_repeat(items: List[List[int]], total_weight: int) -> int:

dp = [0] * (total_weight+1)

for W in range(1, len(dp)):

for w, v in items:

dp[W] = max( dp[W], dp[W-w]+v if w <= W else 0 )

return dp[total_weight]

items = [

[6, 30], # [w_i, v_i]

[3, 14],

[4, 16],

[2, 9]

]

total_weight = 10

total_value = knapsack_with_repeat(items, total_weight)

print(f"{total_value=}")

# total_value=48

Knapsack without repeat

Only difference with “Knapsack with repeat” is, we can take an item at most once.

Sub-problem

Trivial sub-problems are when or the list of items is empty.

We take .

Order

Sub-problems form a grid, row-wise.

With items, time:

, space:

.

def knapsack_without_repeat(items: List[List[int]], total_weight: int) -> int:

n = len(items)

dp = [

[0]*(total_weight+1) for _ in range(n+1)

]

for i in range(1, n+1):

w, v = items[i-1]

for W in range(1, total_weight+1):

dp[i][W] = max(

dp[i-1][W-w]+v if w <= W else 0, # take

dp[i-1][W ] # leave

)

return dp[n][total_weight]

items = [

[6, 30], # [w_i, v_i]

[3, 14],

[4, 16],

[2, 9]

]

total_weight = 10

total_value = knapsack_without_repeat(items, total_weight)

print(f"{total_value=}")

# total_value=46

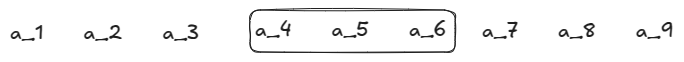

Subarray as sub-problem

Input is and a subproblem is

.

Number of subproblems: .

Chain matrix multiplication

Given a sequence of matrices:

, we want to find the minimum cost to compute their product:

. The cost here is the total count of multiplications. The cost varies depending on how we parenthesize the matrices to carry out the multiplications.

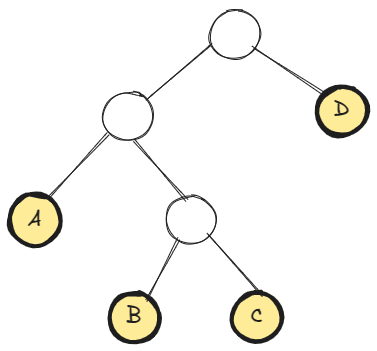

The parenthesized multiplication can be represented as a binary tree. For example can be thought as:

The number of distinct such trees is the number of distinct parenthesizations of the matrices. Say is the number of distinct binary trees with

leaves. Then,

. If we compare

‘s recurrence relation with that of Fibonacci number (

), we see

. In other words, there are at least

different parenthesizations of a sequence of

matrices; brute force checking of each of these is going to be very inefficient.

Sub-problem

Facts about matrix multiplication

- The cost of multiplying matrix

with the matrix

is

. Because the product matrix will have

entries and each entry requires a

-sized dot product.

- Say we have already found the two products:

and

. The cost of multiplying these two products is

.

Say is the minimum cost for multiplying the sequence of matrices:

. Note,

.

The subproblems reside on a two-dimensional grid. Say is the row index and

is the column index. The solution to the original problem is then

and it will be on the last grid-cell on the first row. Also, since

, all subproblems reside on or above the main diagonal. So, the subproblems actually form a triangle.

Order

The size of a subproblem is , because between

and

, there are

different values

can take on. The edges always go from smaller sized subproblems to the bigger sized subproblems. For example, a 3-sized sub-problem can have edges from 2-, 1-, 0-sized subproblems but not from 4-, 5-, etc. sized subproblems. Thus, processing the subproblems in increasing order of size gives us a topological ordering.

Time: , space:

.

def compute_min_mult_cost(matrices: List[List[int]]) -> int:

n = len(matrices)

dp = [

[0]*n for _ in range(n)

]

for sz in range(1, n):

for i in range(0, n-sz):

j = i+sz

sub_min = float('inf')

for k in range(i, j):

sub_min = min(

sub_min,

dp[i][k] + dp[k+1][j] + matrices[i][0]*matrices[k][1]*matrices[j][1]

)

dp[i][j] = sub_min

return dp[0][n-1]

matrices = [

[50, 20], # A: 50-by-20 matrix

[20, 1], # B

[ 1, 10], # C

[10, 100] # D

]

cost = compute_min_mult_cost(matrices)

print(f"{cost=}")

# cost=7000

Leave a comment